JOURNEY TO ITALAQUE Part IV.

An Andean Adventure in Four Parts

By Henry Kuntz

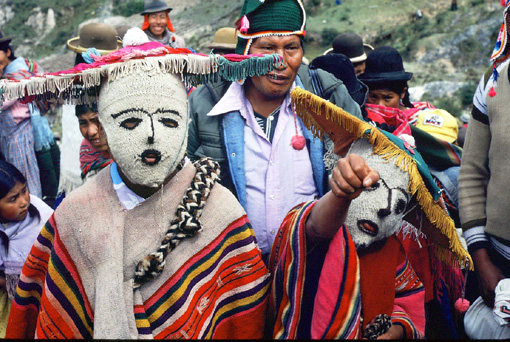

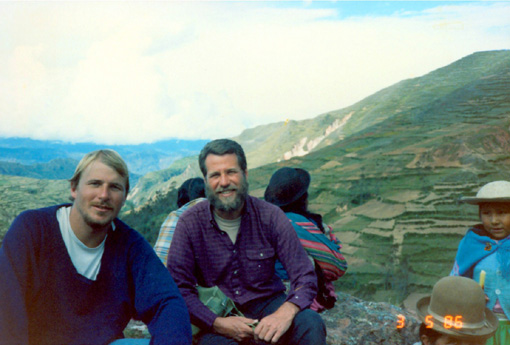

Final Part: Our Strange Journey Back

(Synopsis: With the Italaque festival winding down, afternoon of May 3rd, Patrick and I began our trek back to Puerto Acosta. As night fell, we lost our trail. A light rain began, then snow flurries. Unable to put our sleeping bags down on the wet ground, and unable to see our way forward, we walked back and forth on a single stretch of road the entire night, waiting endlessly for daybreak.)

Almost imperceptibly, the first faint gray light appeared. We now began to move with purpose, seeking to find the trail back to Puerto Acosta. We had scarcely begun our search when snow began falling in earnest. In only a few minutes, the countryside was blanketed in white. It was beautiful to gaze on, even in our weariness, but everything around us became instantly unrecognizable, unfamiliar.

We knew the trail we were looking for wound out of the extensive plain and valley we had hiked through two days earlier. If we could locate the valley, we could get back on the trail. For a while, we thought we had found it. With snow blowing about, clinging to my beard and to our clothes, we wandered far down into a spacious, mountain-ringed flatland that resembled the area we had come through. Our shoes and feet, already wet from the rainy night, became soaked and heavy as we sloshed through the frosty groundcover. We seemed to have uncovered a portion of a trail here or maybe over there, but all paths came to a dead end; there was no way out of this valley save for the way we had walked in.

By the time we had trudged back to the road, three long hours had passed. We had been on that out-of-way rut for fifteen hours. We were exhausted and trying to fend off a feeling of hopelessness. But at least the snow had stopped; slivers of sun poked through the clouds. Since we had camped in this place the night before, we had not seen a single person, a single dwelling, nor any passing vehicle. Then, just as we were beginning to silently ponder the unthinkable, that we might actually not be able find our way out of this place, a big bouncing open bed truck came rattling up the lonesome corridor. We were as much astonished as elated and relieved.

The vehicle, packed with human cargo, was plying the route from Italaque to Escoma, the town we had passed through on our way from La Paz to Puerto Acosta. We climbed aboard while the riders, mostly Indian men on their way to some rough job, stared at the embarrassed and foolish pair of us with amusement. We took it in stride, aware of how ridiculous we appeared in the eyes of those accustomed to the mountains’ ways. Underneath, we felt happy to be alive; because while we had not exactly stared Death in the face, we had caught a fearful glimpse of the Grim One dancing excitedly in the distance.

Less comprehensible and more strange was the treatment we got once we arrived in Escoma.

It was mid-morning when we stepped off the truck into the town square. The sky had cleared; we stood beneath an immense blue dome. A blazing sun was perfect for drying out our shoes, clothes and sleeping bags. We laid our things at the plaza’s edge, then sat and ate the last bit of bread and sardines we had. The humble fare tasted heavenly, whetting our appetite for the proper meal we hoped to have.

We also dreamed of getting some sleep.

As a clock struck twelve, high noon, we roamed the square in search of a room; by chance, we wandered into the town’s only restaurant. A boy began to seat us, but we declined his invitation momentarily to gather our belongings. When we returned, no more than ten minutes later, the establishment’s owner, a taut, broad-shouldered woman of Spanish and Indian descent, stopped us at the door. Flailing her arms and head about, so as not to look at us directly, she haughtily announced that there was no food: “No hay comida, señores!”

We were taken aback. Through an open door, we could see half-empty soup bowls on the tables, patrons dining, and slabs of meat on a long table in the kitchen. It was mid-day, after all, when Bolivians eat their main meal. “Perhaps later?” we inquired. “Sí, tal vez,” she replied, but her voice trailed off, her tone was noncommittal.

We went back to searching for a place to sleep. We discovered the town’s only hotel, a rich red-brown brick and wood edifice two stories tall with an indeterminate number of rooms. The establishment’s proprietor, a slim, pale mestizo with shiny white hair, couldn’t say for sure if anything was available. We should check around 3:00 o’clock, he said.

We hung out in the square for a while; later we tried at the restaurant again. It was the same story.

While we might have chalked our situation up to bad luck or circumstance, the writing on the wall soon became clear. When a small señora in a dank little sundry shop refused to sell us even a roll of toilet paper, claiming she was “out,” while a supply sat clearly in view on an upper bare-plank shelf, we began to get the message.

Why we were being given this message, we had no idea. Several Israelis who had stayed in Escoma and who had boarded the truck we were on a few days earlier going to Puerto Acosta, had not related any bizarre tales of the place. So what could have happened since then? Perhaps we had been mistaken for someone, or taken for U.S. government agents working to eradicate the popular indigenous coca crop. More likely, we were shouldering the blame for some recent social transgression attributed to one or another testy foreigner who had passed through the area ahead of us. Who knew?

Admittedly, we could hardly have looked our best after weathering a night in the mountains, but the town was not big on appearances, and we had not forgotten our manners.

Dutifully, we approached the innkeeper again about a room; the response was a predictable “No hay.”

An hour later, 4:00 o’clock, a truck showed up going in the direction of Puerto Acosta. Almost simultaneously, and with an underlying sense of “Eureka,” Patrick and I exclaimed, “Let’s get out of here!”

But there was a catch. The driver would not risk taking his vehicle over the usual route to the town, portions of which were sunk under three or four feet of water from Lake Titicaca, swollen and expanded beyond its bounds by the season’s ill-fated torrential rains. He would drive a quarter of the way. We would have to walk the rest, a distance of twenty kilometers.

We didn’t think about it; we climbed aboard.

Our fellow travelers were an amenable lot, young and old, men and women, who generously included us in their circle and offered to steer us toward our destination. Patrick and I clung to the wooden railing that enclosed the back of the truck. The clattery rig bumped along a beaten up road until, in the early evening dark, it came to an unsteady halt at the edge of a nameless village. The bunch of us, forty or so, came piling off the truck; people began rapidly moving in the direction of the trail to Puerto Acosta. Most people were not actually going there, but they were able to reach their villages by means of the same path.

A muddy byway skirted the little pueblo. Several houses on its perimeter emitted just enough light for us to avoid stepping into the deep pools of water that were about. From somewhere, we could hear high wispy flute tones; and we could see little decorative touches, colored lanterns and streamers, inside the windows of the houses. As Patrick and I passed by one of the adobe casas, two large Indian women, their hair undone, came straggling out, sobbing uncontrollably. A day’s festivities, and no doubt a bit of strong liquor, had unloosed some long-buried sorrow, attested to now by their wet, streaming tears.

We kept moving, not wanting to separate ourselves from the group going toward Puerto Acosta. We stayed close to two young Bolivian men who were leading the way. The two set a fast but steady pace. Considering the altitude we were at (more than 12,000 feet), the ease with which they maintained their momentum was amazing. Patrick and I pushed hard to keep up with them; the four of us were soon walking alone, having outdistanced everyone behind us. We tried to literally follow in their footsteps. They skipped over rocks and picked their way through the trails’ ubiquitous puddles with a sixth sense, faster and more surefooted in the dark than either of us might have been in the day. All the while, they were smoking cigarettes and carrying on conversation!

For a long time, we hiked the gradual slope of a high ridge that dropped down into a canyon on our left; then, the ridge disappeared, the trail narrowed and became rougher. The night was clear, punctuated by occasional moving clouds.

In our worn state, Patrick and I were hallucinating. We would see distant flashes of what appeared to be mammoth snow-covered Andean mountain ranges.

When we had gotten about three quarters of the way to Puerto Acosta, three hours on, the young men bid us adios and disappeared down a hidden footpath that led to where they lived. Before they left, they pointed us in the direction we needed to go. But we were unsure of ourselves in the dark and waited to see if anyone else might be coming along who was going our way.

Ten minutes later, an Indian man and his son showed up. Their loose white clothing stood out in the night and was girded skirt-like around their waists, leaving their lower legs exposed. They were stooped over due to the heavy burdens they bore on their backs. Each, with their arms behind them, carried a rectangular wooden box, as wide as their bodies and more than half their height, which was secured by means of a thick leather strap that went around the boxes, then over their foreheads. The man’s son was only a boy, but he was uncomplaining, as stoic in demeanor as his father.

Their destination was Puerto Acosta; they didn’t mind us accompanying them. The trail became rocky, went up a little, down a little. Their philosophy of travel was the opposite of that of the young men we had been with. They avoided small puddles, but they walked straight through wide mountain streams or any standing water. We had little choice but to follow, once again saturating our shoes, socks and feet.

An hour and a half later, we arrived in Puerto Acosta. Its normally quiet pitch black streets gave evidence of the town’s ongoing fiesta, with strains of drunken crooning coming from some of the houses.

We thanked the man and his son for guiding us. Then we found our way to the unnamed pension we were staying at. We pushed open the door to our room and stumbled through. Josh sat on a bed reading. Seeing us, he bolted up and stared in disbelief. “Holy Jesus!” he declared. “What’s happened to you?” Before we could utter a word, he left and returned with a large beer and three glasses. That gold sparkling brew was a divine elixir! Then, though we were barely able to string together intelligible sentences, we told him our story – of our trek to Italaque, of the wild native festival, of getting lost in the mountains and the tale of our return. He listened silently, intently, gaping incredulously.

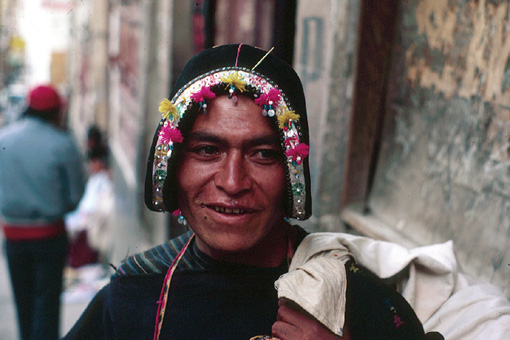

Then he related to us what had gone on in Puerto Acosta. On the first day of the festival, a riotous procession, complete with siku, or panpipe, ensembles, had charged to the summit of the nearby hills. A group of men bore on their shoulders a heavy platform graced with a dazzlingly decorated statue of the Virgin. In the midst of the foray, one of the bearers spontaneously handed his privileged cargo to Josh, an honor which, despite the protest of his aching back, he dared not refuse. God knows, if the Virgin were to have tumbled from her place of glory, there could only have been hell to pay! For two days, the bands had been playing their music on the hilltops and simultaneously shooting off sticks of dynamite! Josh himself had been invited to rehearse with and play in one of the bands. Tomorrow, the festivities would continue with private house parties, to which we were invited.

Splashing ice cold water on myself from a tiny sink that night was never so pleasing. And to actually sleep in a bed again was luxurious.

The next morning, brass bands and panpipe ensembles marched boisterously around the town and the square. They were bound for the inner courtyards of residences where the festival parties were being hosted.

By afternoon, the affairs were in full swing. We hung out where Josh’s band was playing.

The group consisted of over twenty players of small single-row sikus. That made for a big sound coming from the little instruments. Resonance was added by the players simultaneously directing their measured blowing into the center of the band’s round, if ragged, circle. People danced to the fast, syncopated music. Someone beat out time on a great drum to propel the sound along, and two men strutted about, each crashing together a pair of lively handheld cymbals.

There was plenty of beer to drink. Dressy waiters in starched white shirts and black bow ties brought around silver trays spread with glasses of translucent red and green liqueurs whose syrupy ingredients perhaps best remained a mystery. Sadly, there was little to eat that was appetizing, only some bony chicken with the seemingly always dirt-flavored Andean freeze-dried potatoes, or chuño, and white rice of the driest sort.

The following day, May 6, we boarded an early morning truck out of Puerto Acosta to begin making our way toward Peru. It was night when we reached the strait of Tiquina, a narrow stretch of Lake Titicaca where one could cross the lake on a barge, continue to the Bolivian town of Copacabana, then on to Peru. As we reached the strait, enveloped by the consummate darkness we had become accustomed to, we were struck by the glare of bright electric bulbs strung over market stalls on the other side of the water. What a revelation to see the light! Strange and wondrous and so liberating!

Thanks to Martha Winneker for editorial assistance.

Text, photos, and recorded sound Copyright Henry Kuntz. All Rights Reserved.

References

Meisch, Lynn: A Traveler’s Guide to El Dorado & the Inca Empire: Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia. Penguin Books. 1977.

(While reflective of the period in which it was written, Lynn Meisch’s guide remains an extensive and valuable one-of-a-kind cultural resource.)

Bricker, Victoria: Ritual Humor in Highland Chiapas. Texas Pan American Series. 1973.

(The concept of “ritual humorist” comes from this engaging ethnographic study by Victoria Bricker.)