JOURNEY TO ITALAQUE Part III.

An Andean Adventure in Four Parts

By Henry Kuntz

Part Three: The Festival’s Wild Finish; Lost in the Mountains

(Synopsis: Following a daylong truck ride from La Paz to Puerto Acosta and a day’s trek across the altiplano, Patrick and I arrived in the musically renowned village of Italaque, Bolivia, for the May 3, 1986 festival. As the “Feast of the Discovery of the Holy Cross” began on top of a high hill, fantastically costumed musicians came playing panpipes and drums, flanked by two “giant condors.” We were amazed to find ourselves witnessing a rare pre-Inca dance.)

Now the pink flamingoes came flying by!

Or so it appeared, as the headdresses of the newly arriving band, adorned with the plumage of the exotic bird, rose above the gathering at the entrance to the small courtyard and chapel. The feathers stood upright atop broad-brimmed cream felt hats and fanned out in wide semicircles. The ritual headpieces were worn over bright multi-hued Andean knit caps, or chullos. The players’ attire, visible as they passed into the yard’s scant open space, was strange: close fitting navy blue coats over flowing white cassocks. Sheepskins, secured by a cord tied between the hide’s front hooves, were looped over the men’s shoulders.

listen to Second Group (Alto Bamboo Flutes)

The long, punctuated whistles of the musicians’ alto bamboo flutes, twenty of them, sounded like a shrill flock of birds lunging this way and that in patterned rhythmic reverie. Only the vibrantly measured beating of a big round frame drum, loosely and gravely snared, gave ground to the non-stop flight. While a leader made offerings and said obligatory prayers inside the chapel, the players circled the courtyard, rapt in the sounds of their own creation.

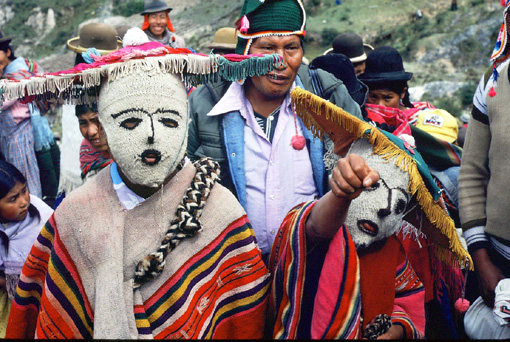

Interspersed among them were two children as kusillus, “monkeys,” taking on the roles of ritual humorists. The function of a ritual humorist is to relieve the serious nature of an event by poking fun at participants (“monkeying around”), often with the effect of reinforcing (by contrast) accepted community values. These types of characters are common at native festivals throughout the Americas. Here the kusillus were devilish sorts dressed predominantly in red, white wool masks pulled over their heads and faces, short rope whips in hand. As the little clowns ran about waving their whips, miniature bells jingled, interjecting a random rhythmic element into the ensemble’s airy song.

Holding their high melody, the musicians wound onto the precipice of the hill where the first band continued blowing mightily into their great sikus, drums still roared, and the giant condors freely soared.

A third band, then a fourth, came briskly up the hill playing bamboo flutes; most were thick three-hole instruments more than a yard long.

Prayers were said and rituals carried out in the courtyard and chapel, then the bands moved through the crowd onto the high precipice.

The two groups, likely from the same community, were similarly attired and played the same music, but separately. Like the previous band, they wore loose white cassocks but without the topcoats; colorful woven belts held the garments in place. On their heads were tied round, stubby, nearly brimless hats richly decorated with a raft of lime, canary, and rose feathers. Curiously, they also wore a black, single-braided women’s wig that fell down their backs but was generally obscured by the scarves around their necks.

Their ethereal and windy tune, lower in range than that of the flamingo-feathered group, was highly stylized, insistent, and trance-like with odd rhythmic twists. There was a quality to it, an elegance even, that called to mind certain types of Japanese or Korean court music. And the players, in their long flowing garments, might have passed for Oriental.

listen to Third Group (3-hole flutes)

Dark-hooded jesters, whose turned-up piggish snouts served as an unsubtle affront to the highfalutin occasion, goaded the bands on; they dryly beat the tightly drawn skins of wooden drums that were strapped over their shoulders.

Then the scene was altered entirely. A band from Italaque showed up wearing western suits and sport coats, ties, and dress hats. They blew vigorously into small twelve-tube sikus, alternating tones between instrumentalists to double the speed of their quick, syncopated song. The music was crisp and precise, directed by shrill peals from a military whistle.

listen to Group from Italaque (small sikus)

When all the bands had moved onto the precipice of the hill, the music really took off.

The groups circled and snaked about one another. Each ensemble continued to play its own swooping, rising, loping mantra right alongside those of the other bands. Drums exploded from everywhere. You might imagine this intentionally created din was like cacophonous noise, but it was more like a wild polyphonic avant-garde circus! And along with the mixes, movements, and interactions of sound, there were whirls and swirls of color from the swaying of the bands, their festive attire and feathered headdresses. The kusillus raced about the area snapping their whips, bells jingling. The giant condors soared majestically high, glided gracefully low.

We expected the Italaque festival to feature a contest between panpipe ensembles. What we encountered was an ancient totemic dance and living ritual whose dizzying array of hues and tones would have been outrageous in a dream.

We wandered dreamlike among the bands and the crowd, joining the locals for chicha, a sour yeasty corn beer, careful to spill a few drops on the ground as an offering to Earth Mother Pachamama before sipping. We spooned down more of the unsavory tuber stew (aftertastes of dirt and dung!) we had eaten for breakfast. Finally, late afternoon, we gathered our things and began the walk back to Puerto Acosta.

Energized by the excursion that had brought us to Italaque, we were excited and eager to undertake the return. We would walk as far as possible before nightfall, sleep outdoors, continue the next day.

It began well enough. In a couple of hours we had climbed completely out of the valley and reached the only road we had passed over on our way to the village. We were not in the same place, however, as when we had crossed it previously. Oh well, we thought, we could easily figure out where we were in the morning. Now, it was getting dark.

We suddenly became aware of how alone we were in this high, remote place. The vastness of the space around us added to the sense of isolation. The world below felt light years away.

We unrolled our sleeping bags behind some boulders to protect us from the wind and crawled in. An hour later, a light but steady rain began. We weren’t prepared. Patrick thought we should attempt to walk above the clouds to escape the rain, to get to where we had been two days earlier when we had traveled this way. But it was so impenetrably black we could scarcely find our way back to the road. We managed, following the low glow of a penlight that quickly gave out.

The narrow camino now appeared only as an unsure outline, and we had no idea which way to go. The rain began turning to snow, and we were getting chilled. We got back into our sleeping bags to warm up, placing them down on the shoddy clay surface beneath us because it seemed like the driest place. For a few minutes it was; then I felt the sudden sensation of ice water on my back. Patrick shouted, “Let’s bail, mate!” and we scrambled out of the runoff from the storm.

We threw the wet bags over our heads and shoulders to shelter us and began walking. While we hoped to reach higher ground, there was little chance of it; we could scarcely distinguish ourselves from the sea of inky darkness surrounding us. We walked, not so much seeing the road ahead of us as imagining it. Only by squinting our eyes were we somehow able to envision it at all. So instead of going to a higher elevation, we found we had gone to a lower one. There was less wind and it was not as frigid; there was light rain instead of snow. We decided to remain there.

The stretch of road we were on was perhaps a hundred yards long and sloped gradually up at each end. We walked that desolate byway back and forth – back and forth! – the entire night just to keep our circulation moving and to fend off the freezing temperature.

Patrick was especially cold. While we were both wearing down jackets, I had on long underwear and a pair of woolen mittens; he was much more exposed. To cover his hands, I gave him an extra pair of socks I had thrown into my bag at the last minute, but they weren’t really enough. Fortunately, he had the hardiness and survival ethos of the sporting life he was accustomed to; he had been a professional soccer player in Australia.

Occasionally the rain would stop but not for long. We only hoped the weather wouldn’t turn worse, and neither of us said out loud our worst fears. We huddled together for warmth and diverted ourselves with simple conversation, exchanging a few words about our families and our lives at home, in opposite hemispheres on opposite sides of the globe. Since we had only known each other for a week, you would have thought we’d have had a lot to say; but it was as if we had known each other forever, sharing an instantaneous bond born of traveling together in an unknown land. So mostly we walked, passing the longest night, waiting endlessly for daybreak. Only the surety of dawn’s coming kept us going.

Next Week: Final Part:

“Our Strange Journey Back”

Thanks to Martha Winneker for editorial assistance.

Text, photos, and recorded sound Copyright Henry Kuntz. All Rights Reserved.