SONIC UPDATES

In Sonic Updates, I am following up on some recent musical commentaries. The remarks below should not be thought of as “reviews” in any usual sense of the word, as my main purpose in writing about music has always been to understand something about it for myself. These are four reports in progress – featuring New Gamelan Sekaten Recordings, Tony Marsh Quartet and Duo, Marc Edwards & Slipstream Time Travel, and Anthony Braxton’s Echo Echo Mirror House Music.

New Gamelan Sekaten Recordings

Gamelan of Central Java XIV: Ritual Sounds of Sekaten (Dunya/Felmay 8168)

1) Guntur Madu – Musicians of Kraton Surakarta – Gd Rangkung (13:58)

2) Guntur Madu – Musicians of Kraton Yogyakarta – Gd Rangkung (27:08)

3) Bawa and Gendhing Terbang (Rebana) – non-sekaten music (12:16)

Recorded during Sekaten celebrations 2004

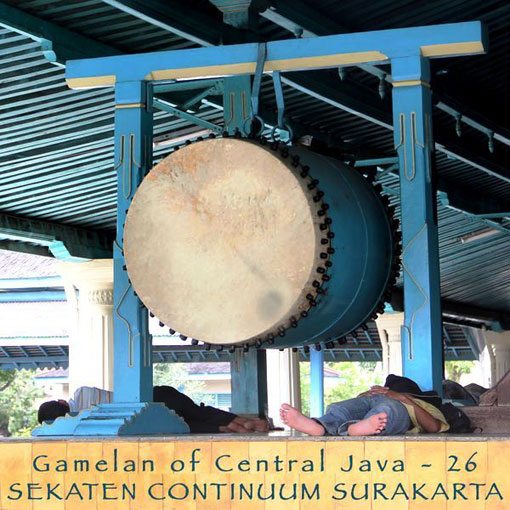

Gamelan of Central Java 26: Sekaten Continuum Surakarta (Yantra Digital/JMN 25)

1) ISI Gamelan Sekati – Gd Rangkung (8:22)

2) Guntur Madu – Gd Bondhet (13:52)

3) Guntur Sari – Gd ‘Peking’ (12:36)

4) Guntur Madu – Gd Glendheng (14:55)

5) Guntur Sari – Gd Rambu (7:14)

Musicians of Kraton Surakarta (Tracks 2-5) and ISI Surakarta (Track 1)

Recorded 2001 (Track 3), 2003 (Track 1), 2004 (Tracks 2, 4, 5)

Recording, mastering, and photos: John Noise Manis

Gamelan of Central Java 27: Sekaten Continuum Yogyakarta (Yantra Digital/JMN 26)

1) Guntur Madu – Gd Rambu (10:50)

2) Naga Wilaga – Gd Orang Asing (12:04)

3) Guntur Madu – Gd Andhong-Andhong (14:57)

4) Naga Wilaga – Gd Atur-Atur (11:29)

5) Guntur Madu – Gd Rangkung (7:40)

Musicians of Kraton Yogyakarta

Recorded 2004

Recording, mastering, and photos: John Noise Manis

In 2009 – to help fill a gap in available recordings of the unusual music of the two Yogyakarta gamelan sekati – I released Java 1997 (HB Earth Series CDR 1). Beyond the on-location recording limitations, the release offered insight into the music’s structure and spiritual character

At that time, only two commercial recordings of the Yogyakarta gamelan sekati existed. Both were made in 1970 by Jacques Brunet (a single track on the LP Java / Historic Gamelans (UNESCO Collection, GREM G1004), and one on the CD JAVA, Palais Royal de Yogyakarta 3: Le Spirituel et Le Sacré (Ocura C560069).

In 2002 – thanks to John Noise Manis and Felmay Records – the first commercial recordings of gamelan sekaten music from Surakarta appeared. Gamelan of Central Java II: Ceremonial Music (Dunya/Felmay FY8042) presented one piece each by each of the two Surakarta ensembles.

Now, additional recordings (from 2001 and 2004) of both the Surakarta and Yogyakarta gamelan sekati have become available: Gamelan of Central Java XIV: Ritual Sounds of Sekaten (Dunya/Felmay 8168); Gamelan of Central Java 26: Sekaten Continuum Surakarta (Yantra Digital/JMN 25); and Gamelan of Central Java 27: Sekaten Continuum Yogyakarta (Yantra Digital/JMN 26).

For the first time, something like a comparative body of recorded work exists. To that end, the newly released pieces have also been identified compositionally. So we can now name previously released but unnamed pieces: on Java / Historic Gamelans (Yogyakarta) Rambu; on Gamelan of Central Java II: Ceremonial Music (Surakarta) Rambu and Andong-Andong; and on Java 1997 (Yogyakarta) Andong-Andong, Rangkung, and Rambu.

You may recall that the original gamelan sekaten instruments belonged to the central Javanese kingdom of Mataram. In 1775 the Dutch split that kingdom into the principalities of Yogyakarta and Surakarta, each principality inheriting a single set of sekaten instruments, which were in fact half of a larger set. Each inherited set of instruments bears the honorific title of Guntur Madu (Honeyed Thunder). Both Yogyakarta and Surakarta then constructed a second set of sekaten instruments to match the inherited ones. In Yogyakarta, the second set is known as Nagawilaga (Fighting Serpent); in Surakarta as Guntur Sari (Essence of Thunder).

The music of these ensembles may be heard publicly only once each year, on the six days and nights prior to the Javanese celebration of the birth of the prophet Mohammed. So as well as it being rare to hear this music, it is difficult – without recorded reference – to place it any sort of evolutionary perspective. The newly released recordings give the gamelan sekaten music exposure, and they offer us selected opportunities to hear it at different points in time and space.

What we first notice are the fairly different approaches to the same compositional material by the Yogyakarta and Surakarta sekaten ensembles. Almost universally, the Surakarta approach is faster, more outgoing and direct while the Yogyakarta approach is slower, more stately and contemplative. This is not simply a matter of the length of the pieces – which may collapse or expand as needed for ritual use – it is the way the music is felt and played differently by the separately evolved and evolving orchestral units.

Compare, for example, the two quite different renditions of the piece Rangkung on Gamelan of Central Java XIV: Ritual Sounds of Sekaten (Dunya/Felmay 8168), one played by Gamelan Guntur Madu Surakarta and the other by Gamelan Guntur Madu Yogyakarta.

You may recall also that all of this music is deeply spiritual in intent, characterized by odd phrasings and intervals, strange rhythmic markings and interjections, and sharp punctuations both on and off the beat.

What we learn from the informative notes to Gamelan of Central Java XIV is that the first use of this on-and-off-the-beat playing (known as imbal) – “metaphorically heard as two spirits talking to each other” –occurred in the piece Rangkung (“Great Soul”). The second oldest composition to make use of this type of rhythmic marking is the piece Rambu (“Oh, my Lord”). These are the only two compositions thought to have been composed specifically for the sekaten ensemble. (My notes to Java 1997 – referencing Brunet – state that there are 14 such compositions, but the reference is incorrectly stated; it should have said that that was the number of compositions in 1970 in the Yogyakarta sekaten repertoire, many of which would have been adaptations of compositions from other genres.)

While the Javanese archetypically attribute these two original compositions to Sunan Kalijaga, one of nine Muslim saints revered for establishing Islam on the island, the ensemble itself – and, one imagines, these compositions – almost certainly existed – in the context of Hinduism – prior to the arrival of Islam (Kunst, referenced by Sumarsam, quoted by J.N. Manis).

We learn also from Sumarsam (Integration and Musical Development in Java, 1995, page 6, quoted by J.N. Manis) that “Sufism dominated the early Islamization of Java. This helped older Javanese traditional performing arts to endure and develop, since Sufism believes in the power of music as a conduit for the union of man with God.”

In making sense of any of the compositions musically, you will want to listen to the interaction between the bonang (the two rows of knobbed gongs played by 1 to 3 players) and the sarons (graded sizes of metallophones played by various ensemble members) and how their roles change and shift within any given piece. One hears patterns of call and response, of mirrored embellishment, and of structural divergence, including movement in counterpoint. And while the bonang tends to dominate early, by the end of the pieces the sarons have come to sonic parity with the bonang, and their roles may have reversed.

There is also one very high-pitched saron that tends to inter-weave between the main parts of the ensemble, inserting additional off-beats, “shadow” beats, or decorative notes, and which may at times even “lead” the ensemble itself.

This latter role you may hear in the piece Andong-Andong (whose title may refer to the sound of traditional Javanese horse-drawn transport). There are also interesting differences in the available versions of this piece. The oldest version, recorded by Brunet in 1970 (from JAVA, Palais Royal de Yogyakarta 3 and played on Gamelan Nagawilaga), is perhaps the most complex. The off-kilter interaction of the sarons with the bonang is sparing and spatial while early on the high-pitched saron takes over the lead from the bonang. In the 2004 version by Yogyakarta’s Gamelan Guntur Madu (Gamelan of Central Java 27) the high-pitched saron sets a lively tempo – the tempo itself exists as a point of musical tension – around which the ensemble interjects more or less “regular” counter beats. The 2001 Surakarta version by Gamelan Guntur Sari (Gamelan of Central Java II) sets a particularly elevated tone and goes against expectation by being a more paced and slower version than its 2004 Yogyakarta counterpart. And in the version by Gamelan Guntur Madu on Java 1997 (piece 1), the high-pitched saron can only be heard deep in the recorded sound while it is the use of the bonang that catches the ear.

I should mention that on the newest gamelan sekaten recordings (Gamelan of Central Java 26: Sekaten Continuum Surakarta and Gamelan of Central Java 27: Sekaten Continuum Yogyakarta) the introductions to most of the pieces have been edited. I understand the reasoning behind this, as the introductions are nearly all identical in terms of notes, and their editing allows the compositions themselves to stand in high relief. Yet the introductions impart an individual and spiritual character to each piece that is not always the same, and I miss not having that.

Obviously you will want to make your own sonic observations and comparisons of all of this music. And the music is such that just when you think you’ve figured one thing out, you may listen again and find you are hearing something new and different.

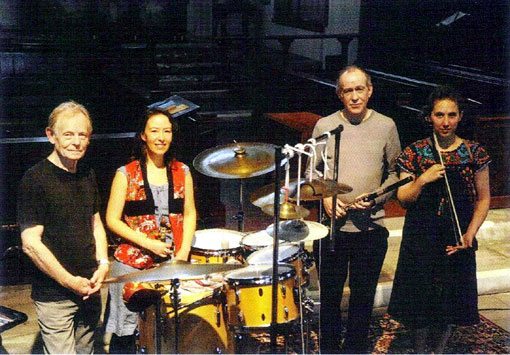

Tony Marsh

Quartet Improvisations

Neil Metcalfe / flute, Alison Blunt / violin, Hannah Marshall / cello, Tony Marsh / percussion

Recorded: August 11, 2010 St Peter’s Whitstable, England.

Stops

Tony Marsh / percussion, Varyan Weston /church organ

Recorded: July 14 & August 7, 2009 St Peter’s Whitstable, England.

One might easily overlook these signature releases by the late English percussionist Tony Marsh.

Relying on neither bombast nor sonic harshness, Quartet Improvisations subtly stands as one of the more sophisticated documents of pure free improvisation.

Along with Marsh, the release features Neil Metcalfe on flute, Alison Blunt on violin, and Hannah Marshall on cello. The players, colleagues in the London Improviser’s Orchestra, share an easy rapport with each other. Their music is a true quartet or four-part music, a collective expression guided by intuition and an empathetic feel for the moving whole. Contour, form, and flow are what stand out in this music in which the musicians contribute fully as individuals while together they create the direction of the quartet. It is a splendid interactive creation.

While one might trace the sound and dimensional aspects of Tony Marsh’s drums back to Milford Graves, the sensibility of this quartet’s music – its language and feel, the way it intertwines – is more European than American (jazz) in origin. You might think of Schoenberg, Berg or Webern. But from Graves – through Marsh – comes an expansive/compositional sense of percussion that adds definition, depth, texture, and color to the music as much as or more than simply propulsion. Or you might say Marsh creates multiple propulsion points that define, shape and clarify the music.

Stops, featuring a series of duets between Marsh on percussion and Varyan Weston on church organ, is a horse of another color. It is an improvisational gem unto itself – as serious as your life on the one hand but showcasing a fair amount of aural slapstick on the other.

Weston turns the church organ inside out, plumbing its depths for wheezy, whistling, reedy sounds – mouth organ like at times – which he disperses inter-dynamically in rollicking, rolling, rhythmic waves. You might picture Keystone cops, soapy romances, writhing damsels on railroad tracks, or sly villains in top hats with coiling moustaches.

Marsh overrides this barely understated comedic drama, multi-layering its directional thrusts with broad fuselages of “significant” strokes; or else he plays straight man to Weston’s serial non-sequiturs, providing sonic punch, punctuation, syntax, and contour.

Interspersed between the duos are four short solo percussion pieces which highlight the formal/tonal range and textural/directional/expressive depth of Tony Marsh’s playing.

Marc Edwards & Slipstream Time Travel

Mystic Mountain: Trouble in Carina Nebula

Marc Edwards / drums & percussion, David Tamura / tenor saxophone, Karl Alfonso Evangelista / electric guitar, Colin Sanderson / electric guitar, Alex Luzopone / combo electric guitar & bass

Recorded October 2, 2015 at The Pine Box, Brooklyn, NY

(Order directly from Marc Edwards: medwards520@yahoo.com)

For the uninitiated, to travel by “slipstream” is to move faster than the speed of light. The concept, drawn from the old “Andromeda” TV series, struck a chord with Marc Edwards who – like Sun Ra – wanted to maintain a musical connection to “math, astronomy, all the disciplines of science and science fiction.”

Slipstream Time Travel’s newest release Mystic Mountain: Trouble in Carina Nebula is a compact (26:48 minutes total), volatile, 3-part stratospheric blast of cosmic energy. From Pre-Launch Preparations through the main Mystic journey to Aftermath: The Fallout!, the music rocks, explodes, whooshes us up and away into the dark (yet supernaturally colorful) unknown universe.

The three throttle-thrust electric guitarists – Karl Alfonso Evangelista, Colin Sanderson, and Alex Lozupone – who Edwards says “drown me out” (hard to imagine, given the charged breadth and power of his drumming), loudly push, pull and dynamically stretch the out-of-phase edges of the music. Tenor saxophonist David Tamura – displaying Brotzmann-like roots – holds steady the shooting-star center of the sonic excursion.

Mystic Mountain: Trouble in Carina Nebula is a gripping, high-energy sound snapshot of the music of Slipstream Time Travel.

Anthony Braxton

3 Compositions (EEMHM) 2011

Anthony Braxton / composer, sopranino, soprano and alto saxophones, iPod; Taylor Ho Bynum / cornet, flugelhorn, trumpbone, iPod; Mary Halvorson / guitar, iPod; Jessica Pavone / violin, viola, iPod; Jay Rozen / tuba, iPod; Aaron Siegel / percussion, vibraphone, iPod; Carl Testa / bass, bass clarinet, iPod

Recorded May 20th, 2011 at Firehouse 12 in New Haven, CT.

3 Compositions (EEMHM) 2011 presents the first studio recordings of Anthony Braxton’s extraordinary new Echo Echo Mirror House Music.

In this kaleidoscopic circus-like musical menagerie, the players use iPods to sample music from Braxton’s entire recorded output while at the same time they navigate instrumentally through selected cartographic scores.

What we learn from Anthony Braxton’s extensive theoretical/philosophical and practical notes on the music is that the players are also provided with a dozen transparencies that may be positioned over the “travel maps” and also on top of each other. These contain visual representations of Braxton’s “language music materials first represented in (his) saxophone solo music.” They suggest to the players ways of interpreting the maps. There are also indications on the transparencies of “pulse velocity (or rate of movement flow)” and of “repositioning” possibilities so that not all of the players are entering into the music at the same time. And along with Braxton as principle music conductor, there are (as in the Ghost Trance Music orchestras) sectional conductors who may independently signal musical directions.

We learn also that this is only the beginning of this fantastical trans-temporal orchestral initiative in which “PAST-PRESENT-FUTURE is approached as one unit of measurement.” Trans-spatial dimensions are on the horizon as well, as Braxton envisions other musicians joining into the music via the internet and even “appearing” with the live performing musicians via holographic projection – “where musicians may contribute to the music from different cities and continents.” It’s definitely a brave new world!

The music on this three-disc set was recorded a day before the live music presented on the Echo Echo Mirror House Victo CD. All of the EEMH pieces are described by Braxton as a “‘state of music’ rather than a composition of music.” Yet each piece has a singular character and takes you on its own marvelous musical journey.

The main differences I hear in the studio-recorded music are in the richness of the musical details and in the thick-layered density of the sound. No matter the iPods, it’s hard to imagine we are listening to the contributions of only seven players.

What is amazing to me, on these and on all of the EEMHM recordings, is the easy organic flow of the music, even with so many things going on and happening at the same time. This is a tribute to the mastery of the musicians, all of whom have been playing alongside Anthony Braxton for some years now and who have been integrally involved in helping to actualize his music and vision.

For more insight into the EEMH music, see Carl Testa’s online article in Sound American 16

Henry Kuntz – October 2016

All Rights Reserved